Rotator Cuff Injuries and Shoulder Pain

Shoulder Pain: A Common Entity

“News Flash”: You will likely have shoulder pain at some point in your tennis career. Why? Shoulder pain in overhead athletes is a common entity. Be it an acute episode following a rocket-like serve/overhead, or a nagging, chronic pain that affects your sleep pattern, the shoulder is vulnerable to injury due to its unique anatomic configuration.

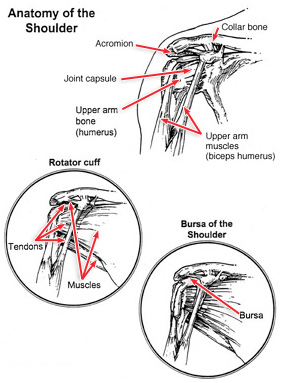

Considered a ball-in-socket joint, the shoulder is unconstrained, typically compared to a golf ball on a golf tee. The humeral head (ball) rests on the smaller glenoid socket (tee); only 25-30% of the ‘golf ball’ is in bony contact with the ‘tee’. Therefore, the shoulder depends on the surrounding soft tissue constructs for support – i.e. the labrum, capsule, rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers. The slightest change – be it an uncharacteristic shot pattern, a change in swing mechanics, or traumatic fall – can create a painful problem. The most common culprit in tennis players is an acute or chronic injury to the rotator cuff muscle-tendon complex.

The rotator cuff consists of four muscles – the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis – that insert on the humeral head as tendons to stabilize and rotate the arm. Anatomically they encircle the humeral head – akin to a shirt cuff around a wrist. Rotator cuff injuries are a common cause of shoulder pain in tennis players of all age groups. They represent a spectrum of disease, ranging from acute reversible tendinitis to massive tears, most commonly affecting the supraspintus. Diagnosis is usually made through detailed history, physical examination, and often, imaging studies. Younger individuals with rotator cuff injuries relate a history of repetitive overhead activities involving the rotator cuff or, less commonly, a history of trauma preceding clinical onset of symptoms. In contrast, older individuals usually present with a gradual onset of shoulder pain and, ultimately, after x-ray and MRI testing, are shown to have significant partial or full rotator cuff tears without a clear history of predisposing trauma. The frequency of full-thickness rotator cuff tears ranges from 5-40%, with an increasing incidence of cuff pathology in advanced age. Cadaveric studies have found that 39% of individuals older than 60 years have full-thickness rotator cuff tears with an even higher incidence of partial tears.

The rotator cuff consists of four muscles – the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis – that insert on the humeral head as tendons to stabilize and rotate the arm. Anatomically they encircle the humeral head – akin to a shirt cuff around a wrist. Rotator cuff injuries are a common cause of shoulder pain in tennis players of all age groups. They represent a spectrum of disease, ranging from acute reversible tendinitis to massive tears, most commonly affecting the supraspintus. Diagnosis is usually made through detailed history, physical examination, and often, imaging studies. Younger individuals with rotator cuff injuries relate a history of repetitive overhead activities involving the rotator cuff or, less commonly, a history of trauma preceding clinical onset of symptoms. In contrast, older individuals usually present with a gradual onset of shoulder pain and, ultimately, after x-ray and MRI testing, are shown to have significant partial or full rotator cuff tears without a clear history of predisposing trauma. The frequency of full-thickness rotator cuff tears ranges from 5-40%, with an increasing incidence of cuff pathology in advanced age. Cadaveric studies have found that 39% of individuals older than 60 years have full-thickness rotator cuff tears with an even higher incidence of partial tears.

Classic complaints of rotator cuff injuries are anterior and lateral shoulder/arm pain when reaching overhead or behind, numbness or tingling in the fingertips, weakness, and/or night pain interfering with sleep. A continuum of pathology from inflammation (tendonitis) called ‘impingement’ to partial or full thickness tears, typically weakness and pain at night indicate the end stage of rotator cuff injury – i.e. a tear.

Non-surgical treatment of ‘impingement’ (tendonitis) consists of NSAIDS, physical therapy to decrease the inflammation and strengthen the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers, and/or a subacromial injection into the inflamed bursal tissue above the rotator cuff complex. Rotator cuff tendon tears can be surgically fixed with an outpatient procedure – often arthroscopically with 3-5 small stab incisions (arthro = Greek for joint; scope = the camera). The success of the procedure depends on several factors such as the quality of tissue and compliance with physical therapy afterwards.

Should you experience any symptoms of these injuries seek medical attention, ideally from a sports medicine specialist, such as an orthopedic surgeon with advanced sports training.